For years the conversation around women in tech has focused on numbers. Too few girls in STEM, too few women in engineering roles, too few female leaders in tech companies. But if we truly examine the history, the data and the mechanics of how the tech industry evolved, the story becomes much more complex. The low representation of women is not a matter of capability or interest. It is the outcome of a system that was never built with women in mind.

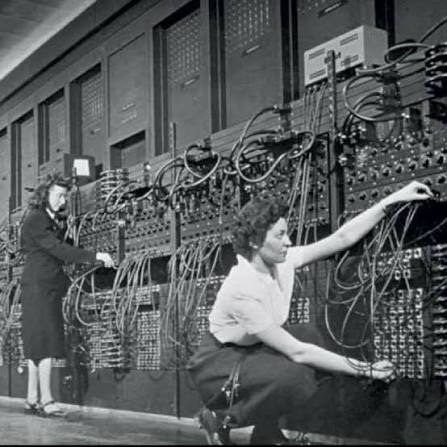

In the early decades of computing, women were not the minority at all. They were the backbone of the field. The ENIAC programmers, the women of NASA, Grace Hopper and countless others formed between 40 and 50 percent of the computing workforce. Programming was seen as analytical and precise work, deeply human and collaborative. Women excelled because the field valued the strengths they brought. The shift happened in the 1980s, when home computers entered the market and were marketed almost exclusively to boys. Within a decade, female enrollment in computer science crashed from 37 percent in 1984 to below 20 percent. Europe saw the same decline. In the Netherlands, we still sit around 17 to 18 percent women in tech roles today. Women didn’t disappear because the work changed. They disappeared because the narrative changed.

Today, the imbalance is even more visible in AI. Only 22 percent of AI specialists in Europe are women. Women are 34 percent less represented in AI research roles. Fewer than one in ten AI leadership positions are held by women. In the Netherlands, the situation mirrors these patterns. These numbers matter because AI is no longer an add-on. It is becoming the infrastructure of how organisations think, decide and operate. When the teams shaping that infrastructure represent only one segment of society, the result is not just unequal representation. It is unequal technology.

The deeper issue is that the tech system itself was designed around norms and behaviours historically associated with male-dominated fields: competitiveness, individual expertise, long-hour expectations, brilliance culture and narrow definitions of “technical ability.” These norms are so embedded that they seem natural, but they shape who feels welcome, who gets recognised and who stays. Women are often judged more harshly for the same behaviours that reward men. Women’s strengths in communication, explanation, coordination, systems thinking and ethical reasoning are undervalued, even though these are exactly the skills AI teams need for responsible and successful implementation.

Psychological safety is another silent barrier. Research consistently shows that many women in tech experience being interrupted, overlooked, under credited or second guessed in technical settings. Even when subtle, these patterns accumulate and drive women out long before they reach leadership. The problem is not just attracting women to tech. The problem is keeping them in tech.

On top of that, the AI systems themselves often reflect the biases of the environments in which they are built. Models trained on data that amplifies male dominant behaviour patterns, career paths or communication styles reproduce those patterns automatically. This has already been seen in recruitment tools, healthcare diagnostics, financial scoring and meeting analytics. Bias is not theoretical. It is mathematical. When the data reflects only part of society, the outputs will do the same.

Meanwhile, young women are still told often subtly that tech requires “natural brilliance,” that AI is only for engineers or that they must fit a narrow profile to belong. Yet the skills needed in the AI decade are broad, interdisciplinary and human: problem framing, ethical reasoning, abstraction, communication, organisation design and pattern recognition. These are not niche abilities. These are strengths women consistently demonstrate across fields.

And then there is visibility. The absence of women in leadership positions, on stages, in AI teams and in public narratives creates a compounding effect. When women cannot see people like themselves in the story, they assume the story is not meant for them. Women in tech are often over mentored but under sponsored, receiving advice but not access, guidance but not opportunities. The ladder is not broken at the bottom. It is broken in the middle.

Economically, organisations are also incentivised to prioritise speed over inclusion during the AI boom. Building AI quickly can feel more important than designing AI responsibly. But this speed first mindset embeds old inequalities into systems that will operate for decades. Inclusion is not a moral bonus. It is an economic necessity. Diverse teams outperform homogeneous teams across innovation, decision quality and customer relevance. AI magnifies these differences even further.

So when we ask why there are so few women in tech, the real answer is that the entire system reinforces the outcome. Education, culture, hiring, leadership, language, visibility, incentives, safety and data all point in the same direction. Women are not missing from tech because they lack ability or interest. They are missing because the system was designed without them.

The AI decade offers something rare. It gives us a chance to redesign the foundation of how work happens. If AI becomes the operating system of organisations, then this is the moment to build a system that finally includes everyone. A system that values communication as much as code. A system that rewards collaboration as much as speed. A system that sees different perspectives as strategic assets, not exceptions. A system where women can lead, shape, design and build without having to justify their place.

The question we should ask is not why the numbers are low. The real question is whether we will use this technological revolution to correct the last one. Women were there at the beginning of computing. There is no future in AI without them at the centre of it again.

Een gedachte over “Women in Tech: The Story we tell, the system we built and the AI Future we cannot afford to repeat”

Reacties zijn gesloten.